FEWS: Flood Early Warning System from Global to Indonesia

FEWS: Flood Early Warning System from Global to Indonesia

In our previous article, we introduced the four foundational pillars of a modern Flood Early Warning System (FEWS)—risk knowledge, monitoring & forecasting, warning dissemination, and response capabilities—as defined by UNDRR and WMO. While each pillar is important, the second—Monitoring and Forecasting—is the technical core. It transforms raw data into actionable warnings and directly influences how early and how accurately a flood can be predicted.

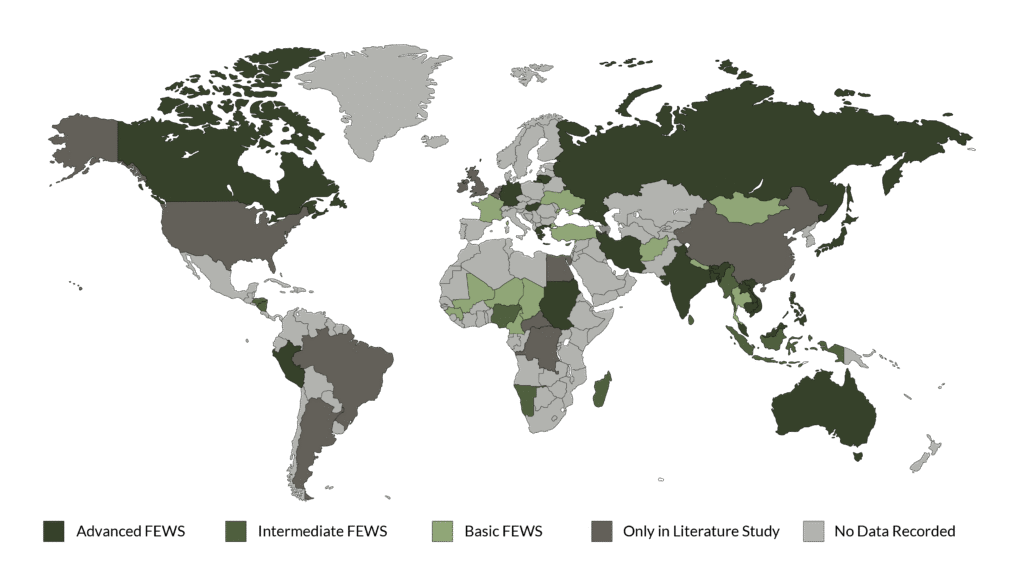

In this follow-up, we focus on how different countries apply this pillar. Drawing on a global study by Duminda Perera (P.Eng)1, we explore how FEWS are classified into Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced systems. This lens reveals both disparities and progress in global flood forecasting.

Table of Contents

ToggleI. Flood Early Warning System (FEWS) from the Global Perspective

Building on the UNDRR framework, the Monitoring and Forecasting pillar plays a key role in generating flood warnings. To understand its global application, Duminda Perera studied FEWS in 47 developing and 6 developed countries.

His study categorized FEWS into three levels—Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced—based on how flood warnings are generated and the technologies used as seen in Figure 1.

A. Basic FEWS

At the most fundamental level, Basic FEWS rely on minimal technology. Typically, these systems collect data manually and use informal communication methods. Consequently, flood forecasts are qualitative, based on observations like upstream water levels. Importantly, they do not use scientific models or real-time data processing, which significantly limits forecasting accuracy and lead time.

B. Intermediate FEWS

Intermediate FEWS add more technical capability. They access real-time rainfall and river data, improving awareness. However, they lack flood modeling tools. Warnings are issued based on expert interpretation and past experiences.

C. Advanced FEWS

Advanced FEWS use telemetric data collection and automated real-time monitoring. They apply hydrologic and hydraulic models to predict when, where, and how severely flooding will occur.

The study found that 43% of systems were Advanced, 38% were Intermediate, and 19% were Basic. While it’s promising that many countries have reached advanced levels, over half still rely on less capable systems. This highlights a global gap in flood forecasting.

One major barrier to advancing FEWS lies in the limited resources and technical capacity available in many developing countries2. In particular, these nations often struggle with insufficient skilled personnel, inadequate data infrastructure, and constrained funding for advanced forecasting tools. As a result, these limitations directly impact the accuracy and timeliness of flood warnings, ultimately reducing communities’ ability to prepare and respond effectively3.

II. Flood Early Warning System (FEWS) from the Indonesia Perspective

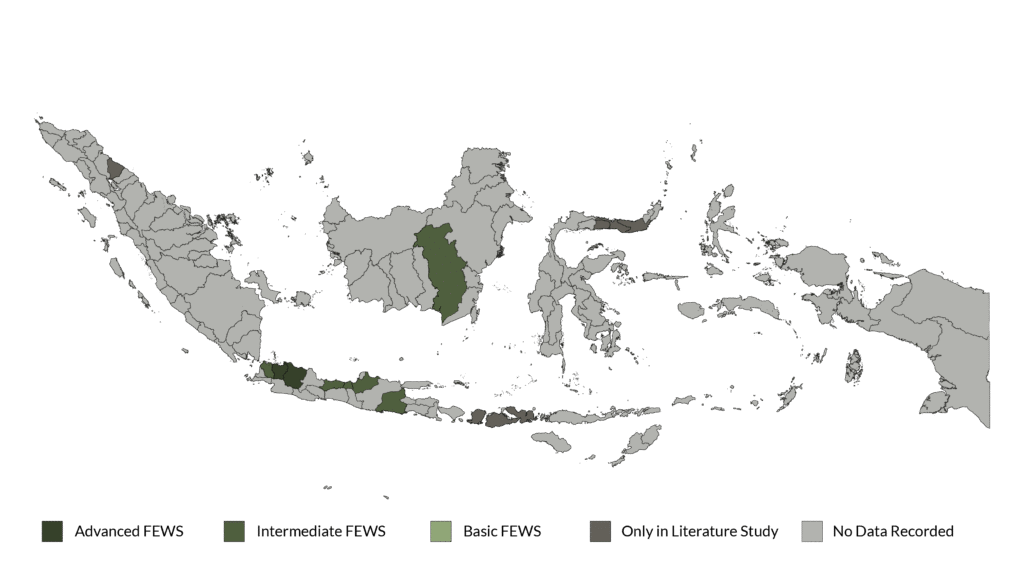

Similarly, Indonesia reflects the global trend. As one of Asia’s most flood-prone nations, it faces frequent and severe flooding. However, many of its River Basin Organizations (Balai Wilayah Sungai or BWS) have not yet fully integrated FEWS into their routine flood risk management practices, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Most BWS units operate at the Intermediate level. They use real-time data from rainfall and river gauges. However, they still lack flood modeling systems. As a result, warnings depend on threshold exceedance and expert judgment. This approach limits both lead time and accuracy.

Some BWS units have begun using real-time data with physically based numerical models. These models can simulate flood scenarios and improve prediction. However, they come with operational challenges. The models often require high computing power and long processing times—sometimes several hours. This makes it difficult to issue timely, updated warnings during fast-moving flood events.

These systems meet many technical standards for Advanced FEWS, but they remain partially manual and slow to respond. In practice, they operate in a transitional stage—technically advanced, yet not fully optimized for real-time decisions.

III. Conclusion

The global classification of FEWS shows a clear divide in forecasting capacity. Many developing countries, including Indonesia, still rely on Basic or Intermediate systems. While progress toward Advanced FEWS is visible, challenges remain—especially in real-time modeling, automation, and institutional capacity.

In Indonesia, most BWS units depend on threshold-based alerts, limiting the system’s effectiveness. Closing this gap requires more than just technology. It demands investments in skilled personnel, robust data infrastructure, and streamlined operations. Strengthening these areas is key to creating more responsive, people-centered FEWS that protect lives and reduce risks from climate-driven flooding.

References

- D. Perera et al., ‘Flood Early Warning Systems: A Review Of Benefits, Challenges And Prospects’, United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, Aug. 2019. doi: 10.53328/MJFQ3791. ↩︎

- W. A. Hammood, R. Abdullah Arshah, S. Mohamad Asmara, H. Al Halbusi, O. A. Hammood, and S. Al Abri, ‘A Systematic Review on Flood Early Warning and Response System (FEWRS): A Deep Review and Analysis’, Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13010440. ↩︎

- J. Cools, D. Innocenti, and S. O’Brien, ‘Lessons from flood early warning systems’, Environmental Science & Policy, vol. 58, pp. 117–122, Apr. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.01.006. ↩︎

About Author

Tom, Ir. S.T., M.Sc., IPP.